On reading scientific articles (June 1, 2015)

I have created a shared folder with Computer Science articles I read, understood and liked. At the moment, there are two items in there, but will be more over time. It’s not a surprise that both of them deal with the question of engineering a system as large as a programming language infrastructure and runtime and staying sane — this is a question that occupies lots of my thinking lately (I don’t know the answer yet, but promise not to withhold my findings). Here they are:

- P. Li, A. Tolmach, S. Marlow, and S. P. Jones, “Lightweight Concurrency Primitives for GHC”, in Proceedings of the ACM SIGPLAN workshop on Haskell, 2007;

- K. Wang, Y. Lin, S. M. Blackburn, M. Norrish, and A. L. Hosking, “Draining the Swamp: Micro Virtual Machines as Solid Foundation for Language Development”, in 1st Summit on Advances in Programming Languages (SNAPL 2015), 2015.

This does not mean, of course, that I only read two articles in my life. It’s just that these two I understand much better than the others and I see how they can immediately be useful in my programming practice. Understanding is a key point here: I remember that during my PhD time my approach to scientific articles was utterly wrong. Here are few rules I learned over time:

- Reading and understanding abstract is a prerequisite to even attempting to read an article. There’s a video of one of the Don Knuth’s lectures where he famously answers a question on performance of some tree-based algorithm from the audience and says something in the vein: “I remember seeing an article describing recent advances about this algorithm, but authors didn’t describe performance limits in the abstract, so not sure.” Abstract absolutely must contain each and every key important moment of the entire article.

- One consequence of the above is that there must be articles out there describing important things, but not doing well in their abstract and being completely overlooked because of that. My attitude towards that is sad acceptance: it is simply not possible to assume the best about every article and spend time reading it anyways when article’s abstract is not clear or not exhaustive.

- At the university I read articles trying to get an answer to what-questions: “what kind of new things people work on?” The better question, the way it seems to me now, is how-question: “how do people do those things they do?” The crucial difference between the two is that the second one implies at least a brief familiarity with the field for which the article is written. What-questions, I now think, are better answered on other media, like textbooks.

Couple of good videos I watched lately — 2 (May 26, 2015)

Big Data is (at least) Three Different Problems. Michael Stonebraker, the most recent recipient of ACM Turing Award, in his usual charismatic manner addresses the most common real (as opposed to imaginary) problems arising when dealing with large amounts of data. Tons of valuable insights about modern databases.

Facebook’s iOS Architecture. Facebook people talk about implementing Facebook app on iOS. You can clearly tell that classical MVC approach is terribly outdated when using it to build apps of the complexity you see in 21st century. It’s not that mobile development is inherently difficult, it’s just gets entangled and messy very quickly as the apps grow.

The world’s most complicated software (May 19, 2015)

A typical software developer in a company possessing some level of technical sofistication routinely switches between abstraction levels during a working day. He or she may go from reasoning about product structure on a web page level to the intricacies of file allocation in their database system. Those dealing with some sort of message processing can switch from a byte-level layout of the protocol messages to a more general view of interconnected queues within the system — you get the drift. From the very early days of being in the profession, programmers are told that abstraction is the key to fighting complexity natural to all software. It’s only after spending few years in the profession, some may discover that few domains are surprisingly resistant to abstraction alone. Without the only tool to fight complexity, developers are left to accept the difficulty of the field as a given. I’ll give an example of a truly difficult problem.

Meet the calendar, the world’s most complicated software.

I’m talking about a product like Microsoft Outlook (actually, its calendaring part and the server). On a first sight, there’s nothing special about it, but if you try to think about it, complexity starts manifesting itself from a very basic level. The interaction protocol between participants trying to agree on a meeting is surprisigly hard to get right. For example:

- When someone receives a meeting invitation, should it be shown to him if a meeting has already passed? How do we detect this (note that we should take time zones in consideration, including the cases when participant is not in his default time zone)?

- When someone proposes a new time for a meeting, but it can’t be sent because the participant was offline should we try re-sending it when participant goes online? What about if the meeting time has already passed? What if not, but his proposed time did?

- What about the time zone changes? If the participant changed a zone, should we reschedule his events? What if all participants changed the time zone? What would be the time zone of the newly proposed events? Of the changes into existing events?

- Should we, once the participant goes online, notify him about the changes to the events that were not accepted by the participant because he was offline? What about the already passed ones?

And so on with an added inherent complexity of dealing with time zones. Calendar is a classical distributed system with participants being people within the same organizations using it simultaneously. Participants can be offline for extended periods of time; they must find consensus on timing of the group events using some reasonably robust protocol; they move around. You probably noted already that part of the problem is the difficulty in specifying it correctly — you’ll have lots of fuzzy and vague sentences with “except” in your specification, rendering almost all your abstraction skills useless. The difficulty of developing a calendar suite differs from the difficulty of your typical job ad’s “hard and interesting problem” in the same way as your morning 2 km jog differs from doing an Iron Man.

If you made a note to yourself never to work on calendar suites, here’s the second most complicated software in the world: library dependency manager. It does not have to deal with people as participants, but is just as full of fuzzy specs: how to handle conflicting (or broken) transitive dependencies, non-mandatory ones, source vs. binary, etc.

Would you want to work on a calendar suite or a dependency manager?

Venice–San Francisco (May 11, 2015)

Everyone who has ever visited Venice as a tourist probably went there with some limited baggage of knowledge about the town. A former center of very powerful Venetian Republic is, as the modern story goes, now full of tourists, almost abandoned by locals, sinking. Reality is, of course, much less grim. When I stayed there in March — it’s the low season there — Venice presented itself as a very lively small town. You stroll around and see kids return from school across the bridge of Calle Bandi in Cannaregio and groups of students from the nearby Academy of Fine Arts playing guitar in Dorsoduro.

One comparison held very strongly on my head the entire time I spent in Venice. What I saw around was, figuratively speaking, what San Francisco will look and feel like in three or four centuries. Bounded by water on almost every side, it’s now just as restrained from further growth and almost as wealthy compared to its modern peer cities now as Venice was at its heyday. In the coming centuries the technology — that San Francisco will ultimately represent — will only grow in importance in everyone’s life and will help it prosper further. The best artists will lend their skills to making the future San Francisco the most refined city for those living there. The unstoppable gentrification will continue to purify the city fabric, eventually turning it into something as beautiful and uniform as Venice’s Centro storico.

It will all be fine for San Franciscans until the technology will stop to matter (because everything eventually does). Maybe the new human psycho-powers will be discovered in, say, Cologne — it for sure will be Germans with their sense of irrational who will do it, — rendering the entire technology industry obsolete. After the period of San Francisco decline we’ll visit it, marvel at the hills and the architecture, and then will all be looking for “non-touristy typical San Franciscan restaurant”.

Apple Watch (May 4, 2015)

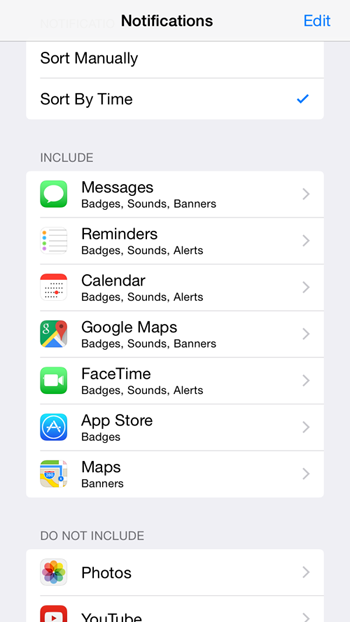

Can’t understand what’s the fuss with Apple Watch overwhelming people with constant distracting notifications. Notifications can easily be disabled. This is what my (and any reasonable person’s) notifications settings screen looks like.

Calls, texts, things to do, navigation, updates. That’s all; Twitter mentions can wait, Instagram likes can wait, even email can wait. Below the fold there are something like hundred and fifty apps, all of which were willing to get their share of my attention and which I decided to check on my own schedule. Because it’s the phone that belongs to me, not the other way around.